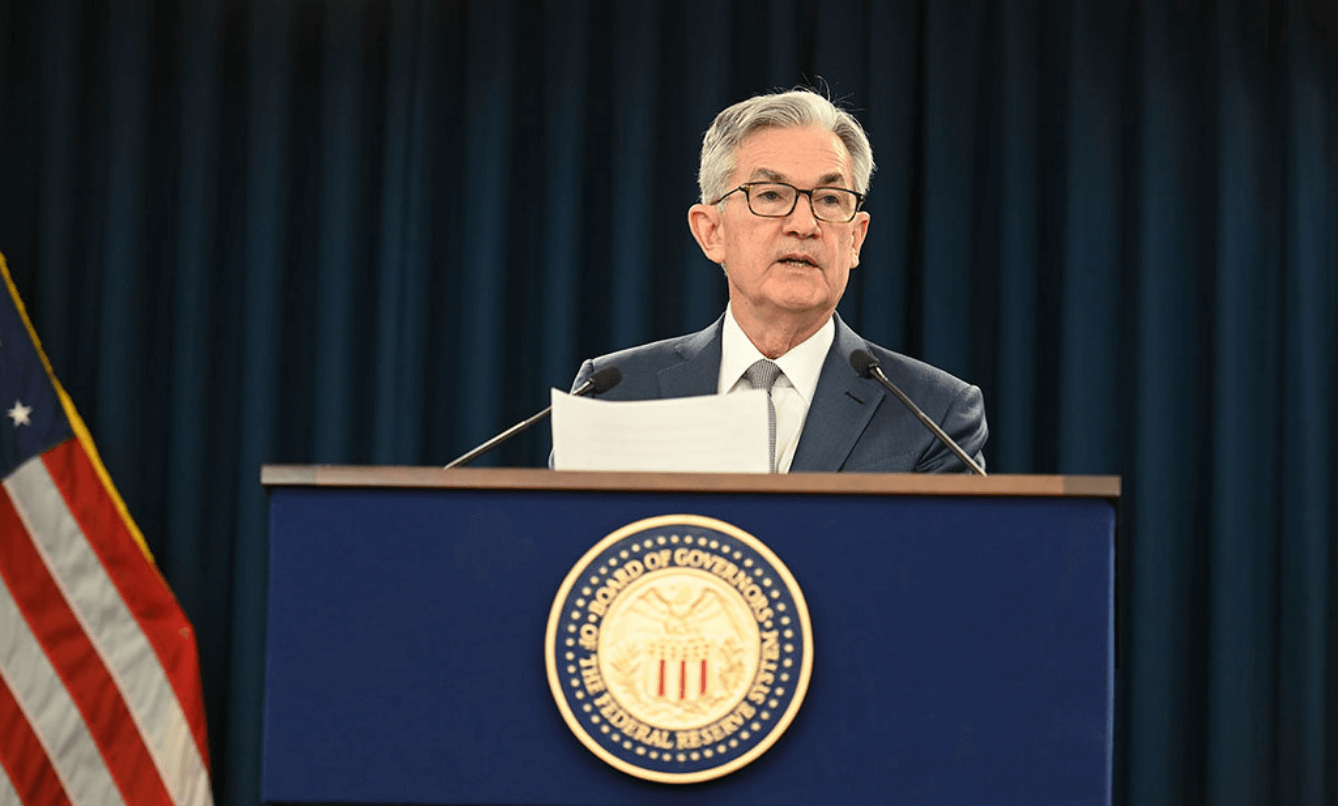

The Federal Reserve’s September meeting wrapped up on 9/22/21 with a statement followed by commentary from Chairman Powell. After much speculation and anticipation, we are still “almost” there. Almost ready to take the training wheels off this heavily “administered” economy. The Fed stepped in to stabilize the economy as we faced the global pandemic last year and effectively kept the economy upright by adding training wheels for balance. Those training wheels included low interest rates, expansion of its balance sheet and several other measures that led to purchases of investment grade and high yield corporate debt and provided a boost to global liquidity to keep markets functioning. While the monetary turning-point we face may be ever so slight, it is a turn, and we won’t be able to rely on the training wheels anymore. Fundamentals will matter again, and investors would be wise to consider how the investment landscape is likely to change going forward. We will tackle this in more detail in our Quarterly Client Deck, Tactical Memo and Stress Test updates in the weeks ahead. The remainder of this memo is included to provide the latest context from the Fed including the important data points that will affect decision making.

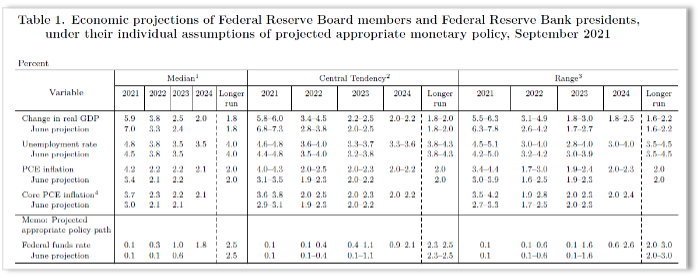

With the caution of a doting parent fearing a skinned knee or a bruised elbow, the Fed inches closer to removing the training wheels on the economy, hoping it doesn’t prove to have acted too early. The Federal Reserve will modulate its policy decisions around two frameworks, one for when they would begin to reduce the current $120 billion in monthly bond purchases, and the second related to when they would raise interest rates. Tapering and interest rate hikes will be determined independently, but both are dependent on the same two factors: inflation and employment. The table below from the Federal Reserve highlights current expectations for GDP growth, employment, inflation, Fed Funds rates and how they compare to their prior forecasts from June. This data confirms the current consensus view that unemployment is expected to continue to improve, the inflation rate is expected to moderate, as is GDP, and that the Fed intends to keep interest rates low for some time to come.

Source — Federal Open Market Committee projections 9/22/21

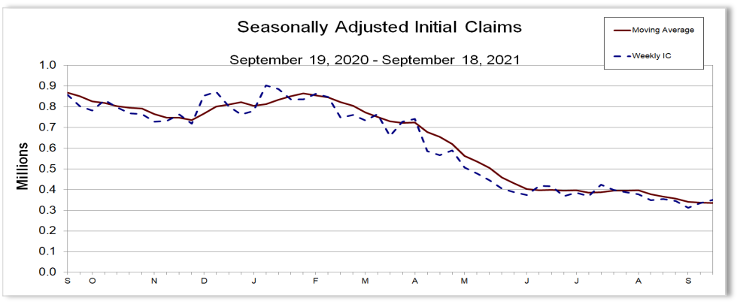

Tapering bond purchases is dependent on a “substantial” improvement in employment relative to where things were at the end of 2020 and inflation expectations of at least 2% going forward. Chairman Powell indicated in his press conference that these conditions have been met, paving the way for the Fed to announce at one of its next meetings (November or December) its tapering plan. Having said that, employment data released the day after their statement shows a slight pick-up in unemployment claims (351k vs expectations for only 317k and previous of 335k) and an increase in continuing claims from 2.714 million last month to 2.845 million. The 4-week moving average, however, continues to show initial claims in decline.

Source — U.S. Department of Labor (4-week moving average)

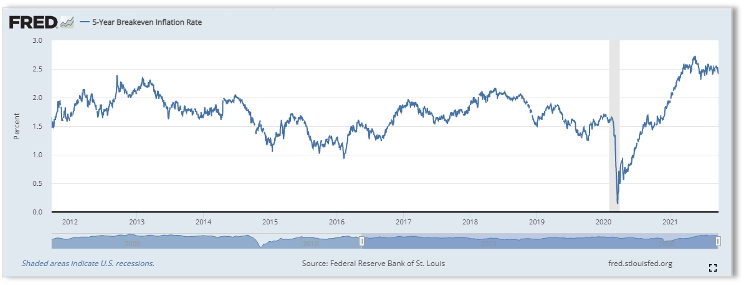

The most relevant data the Fed will consider at its November meeting will be the September new jobs report which will be released in October. Chairman Powell noted that inflation rates have surpassed their target levels, and the Fed Governors on average still believe that inflation will drift lower towards their 2% target in the next year or two as supply chain issues begin to resolve themselves. It seems that Chair Powell did make a subtle distinction in his comments between actual reported inflation and inflation expectations, focusing on the latter as the key metric to consider. We include a look at the St. Louis Fed’s 5-year Breakeven Inflation Rate calculated by looking at the difference in yields between nominal and inflation-protected Treasury securities. This shows expectations currently hovering in the 2.5% range for the next five years.

Source — Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Chairman Powell did not detail the specific plan for tapering but suggested that it would start before year-end and that he expects the Fed would end its bond purchases by mid-year 2022. He reiterated that current plans do not include a reduction in the total size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

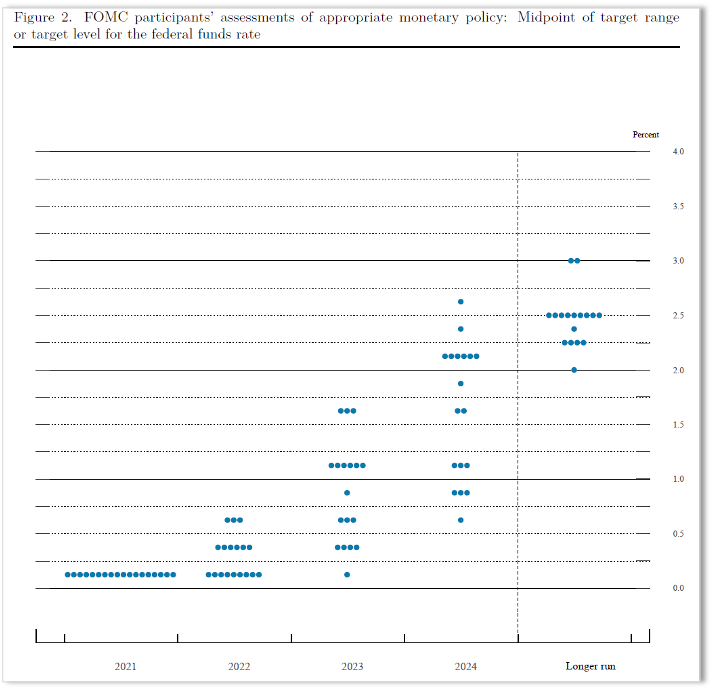

“Liftoff”, as Chairman Powell refers to when the Fed might start raising interest rates, is also determined based on inflation and employment metrics. Achieving inflation of “moderately higher than 2%”, in his words, was the goal along with reaching maximum or “full” employment, which would coincide with an unemployment rate of approximately 3.5%. Only then would the Fed consider raising interest rates, with the caveat that they are keeping a close eye on upside surprises to inflation that may require earlier action to address. The majority of Fed Governors expect “Liftoff” to begin in 2023. Chairman Powell also emphasized that he anticipates the Fed Funds rate to remain below the long-term expected rate of 2.5% at least through 2024. The Fed’s “Dot Plot” shows that expectations for future interest rates remain wide, highlighting the difficulty in predicting the precise path from here.

Source — Federal Open Market Committee 9/22/21

If you have any questions, please contact us.

Please see PDF version of this article for important disclosures.