If I am going to buy a house, should I compare the listing price to other like houses in the neighborhood? If I am planning on buying a car, should I request a breakdown of cost from the dealer and look at the prices of other similar cars? I could hurriedly make these purchases and, perhaps, everything will work out. However, I think we would all agree that considering value is a significant component of any large ticket purchase. Given the importance of value, why is it so often overlooked when it comes to investments? Particularly, alternative investments.

How is the Accuracy of Investment Valuations Important?

Earlier this year a client reached out to obtain our thoughts on a hedge fund they were considering for investment. The Fund had phenomenal returns, 100%+ annualized over the last 3- and 5-year periods. The vehicle provided monthly liquidity upon 180-day notice with a 1-year soft-lock; fairly standard liquidity provisions for a hedge fund. What caught our eye was that the Fund had over half of its investments in private companies that were NOT publicly traded. The monthly liquidity offered to investors, along with the significant proportion of the Fund’s assets in non-publicly traded securities made valuation, amongst other issues including a potential mismatch between the Fund’s liquidity terms and the liquidity of the underlying investments, a key part of the due diligence process. Some of the vital questions to be considered were how does the Manager determine a fair market price for the private assets in the Fund? How do we know that an investor’s entry price is commensurate with the actual value of the Fund’s investments? Again, the Fund does not hold a portfolio solely consisting of public stocks, like Amazon or Apple, that are priced daily by the public markets. It holds a combination of easier to price publicly traded assets and private investments where the value is more difficult to ascertain. Additionally, it is common for hedge fund managers to keep 20% of the Fund’s realized and unrealized gains (otherwise known as carried interest). If half the positions in the Fund are not publicly traded, an investor should understand how the private securities are valued before they agree to the Manager taking 20% of the unrealized gains.

What is to say that the fair market value of the private assets is not 20%-30% less than where the Fund has marked them? As this paper will more fully address, the Manager is economically incentivized to value those positions as high as possible. The higher the assessed value, the more profits the Manager captures through their carried interest fees.

In this third edition of our white paper mini-series on due diligence red flags in alternative investments, we are going to focus on valuation. Specifically, we are going to address the concept of Fair Value Measurement (“FVM”), review best practices for valuation, walk through a case study that focuses on the failure of valuation processes, and present key questions to ask during the due diligence process. We will close the paper by discussing two examples that highlight current valuation trends.

By the end of this paper, we hope to equip the reader with a sufficient understanding of the valuation process for alternative investments so they can better identify and mitigate potential red flags during their own due diligence activities and ensure a safer allocation of investment capital.

Fair Value Measurement

International accounting standards define Fair Value Measurement (“FVM”) as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date (an exit price). When measuring fair value, an entity uses the assumptions that market participants would use when pricing the asset or the liability under current market conditions, including assumptions about risk.”[i] Managers of alternative vehicles, whether they be hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, real estate, private credit, etc. must adhere to this concept of FVM when valuing the securities held in their Funds. Fund Managers cannot simply keep private assets at cost or keep the price constant over multiple accounting periods, aka stale pricing.

This is particularly relevant during times of market volatility. They must assign a value to the assets in their Fund that would equate to the price that they would receive if they were to sell the assets. If not, their auditors will refuse to provide a clean audit opinion of the audited financial statements[ii].

Given this backdrop, how does Fair Value Measurement work in practice?

While the details are beyond the scope of this paper, the overarching process is straightforward. To begin, a Fund’s assets are grouped into three buckets[iii]:

- Level I: Marketable securities that are primarily traded on a securities exchange, e.g., publicly traded stocks and developed world government debt (US Treasuries). The fair value is determined to be the last sale price on the determination date, e.g., the closing price of Apple common stock on the last trading day of a given year.

- Level II: Corporate bonds, convertible debt, and warrants. Securities where fair value is determined using valuation models in corroboration with observable market data, e.g., bid-ask quotes from brokers or market makers, implied volatilities, and credit spreads.

- Level III: Equity in privately owned entities. Pricing inputs are unobservable, and determination of fair value requires significant judgment or estimation from management.

The valuation process for Level I and II assets is clear-cut. However, Level III assets are hard to value, and in many instances, more of an art than a science. There are three primary methodologies used to estimate value for Level III assets: Private Transaction multiples (looking at the prices for which comparable companies were acquired), Public Transaction multiples (looking at the price to earnings or price to sales multiples of comparable publicly traded companies) and the Income Approach (using a discounted cash flow analysis). [iv] The first two approaches would be analogous to a homeowner trying to value their home by looking at the recent sale prices for other homes in their neighborhood (private transaction multiples) or looking at the price per square foot of similar homes and applying that price ratio to the applicable square footage of their home (public transaction multiples). In summary, publicly traded assets are valued using their closing price. Securities that do not trade on an active exchange, but frequently trade between market participants, e.g., bonds, are valued through a combination of looking at bid/ask quotes for similar securities and other observable inputs like credit spreads. Level III assets have values that are estimated through the various techniques described above, e.g., transaction multiples, trading multiples, or a discounted cash flow analysis.

Alternative Investments Valuation Best Practices

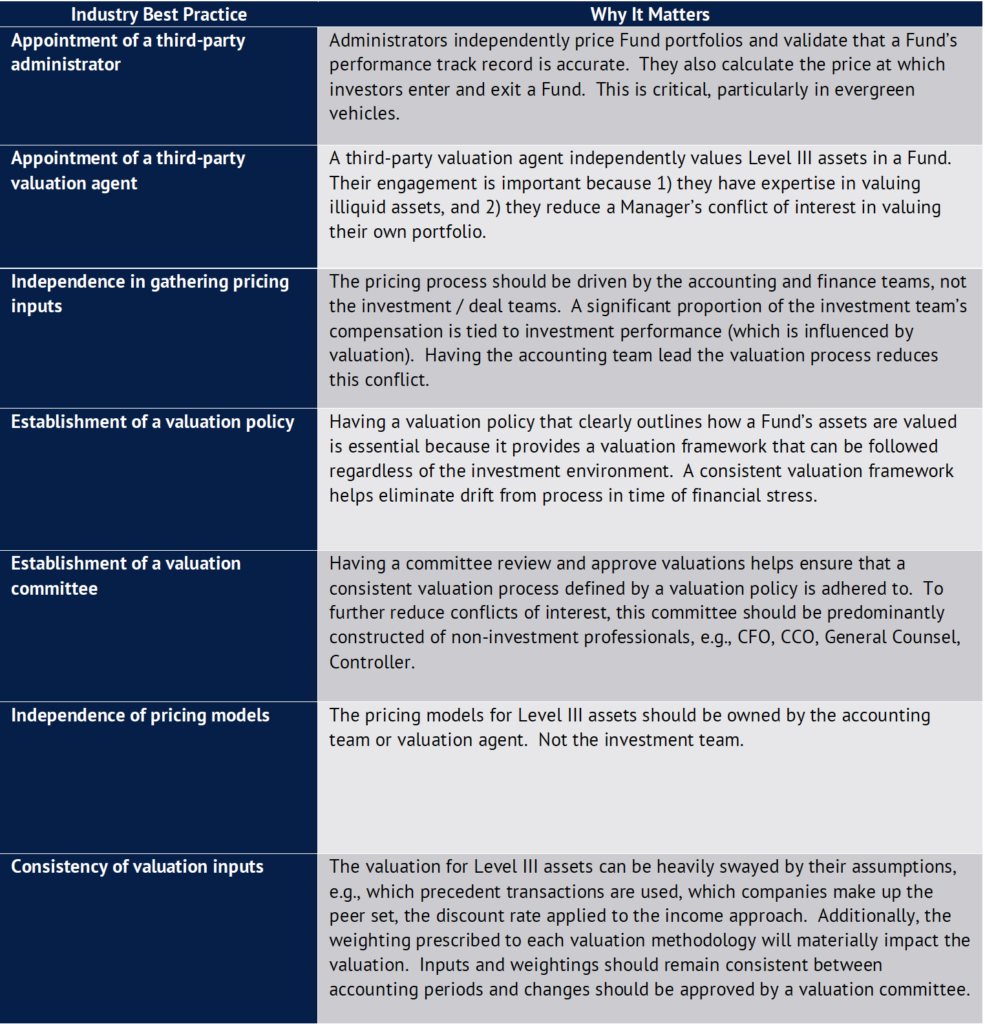

Now that we have an appreciation for 1) how valuation matters and 2) how values for various assets are assessed, it will be helpful to develop an understanding of how an investor can determine whether a Manager has sufficient processes in place to adequately value the assets held in their Fund. Provided below is a quick reference of best practices and why those practices are important. The predominant theme is mitigating conflicts of interest.

In a typical evergreen or hedge fund structure, the Manager assesses two different types of fees: 1) management fees – these fees are based on the assets under management within the Fund and 2) performance fees – the Manager takes a cut, usually 20%, of the Fund’s gains, both realized and unrealized, over a calendar year[v]. Both fee streams are directly tied to the valuation of a Fund’s underlying investments, and that connection between the valuation of the Fund’s assets and the fees that accrue to the Manager of the Fund, particularly the performance fee, creates a conflict of interest for the Manager. Good valuation frameworks are designed to mitigate part of this conflict of interest so that when investors are 1) assessed fees or 2) enter or exit a Fund, they can have confidence that the fees being charged or prices they are transacting at are fair and reasonable.

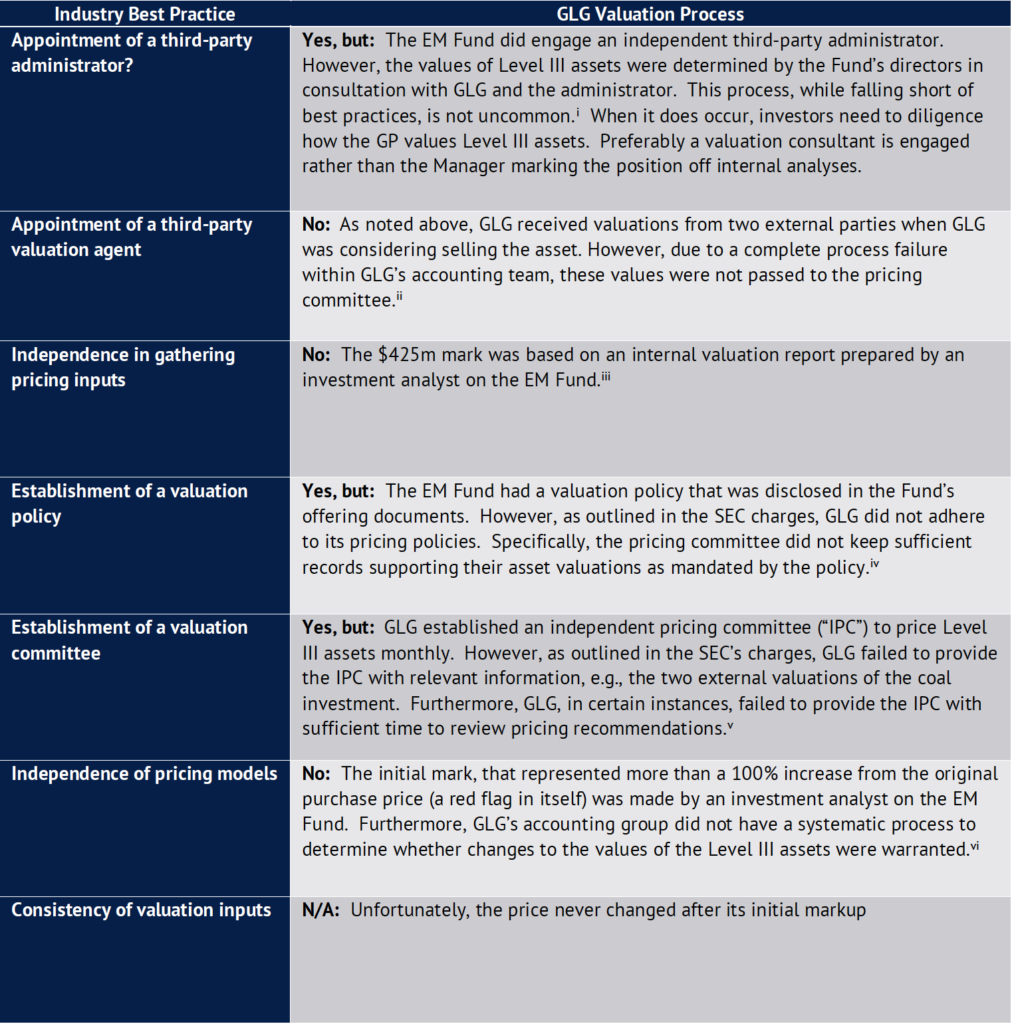

Case Study – GLG Partners

GLG Partners, a UK based asset manager with operations in the US (“GLG” or the “Manager”), was charged by the SEC in 2012 with internal control failures that 1) led to the material misstatement of a fund’s NAV, the GLG Emerging Markets Fund (“the EM Fund”) and 2) inflated fee revenues for the Manager[vi]. At the heart of the matter was Sibanthracite, an overseas coal company, that the EM Fund purchased a 25% stake in for $210m on March 20th, 2008. On March 31st, 2008, only eleven days later, GLG marked the position up to $425m, a +100% increase. [vii] GLG then kept that valuation flat for the next two years, despite the fact that in the intervening period 1) the global financial crisis occurred, 2) coal prices collapsed, and 3) the Manager received valuations from two external parties in January 2010 and September 2010 that valued the stake at $350m and $240m, respectively. [viii] GLG’s stale pricing caused the EM Fund’s NAV to be overstated by roughly $160m for 25 consecutive months. As a result, investors paid excess management fees of $7.6m that should have never been charged if the valuation process had been more robust.

This case study centers on the complete failure of GLG’s valuation process. To better highlight these shortcomings, let’s contrast the Manager’s pricing practices, as detailed in the SEC order, relative to the table of best practices introduced earlier in this paper. We hope that this comparison can illustrate how an investor can better detect these failures in advance of making a potential investment:

The GLG case study highlights the importance of diving into specific asset valuations during the due diligence process. While this exercise is not a magic elixir, it does bring forth several key aspects of a Manager’s valuation process (or lack thereof). For example, how did valuations change over time relative to broader markets; who owned the valuation models; did the valuation committee have supporting materials to corroborate the ultimate price they approved, etc.

Questions to Consider During the Due Diligence Process

In our introductory paper, we posed various questions pertaining to valuation that investors should consider when conducting due diligence.

These questions are reproduced below along with various remedies we have implemented:

1. If you subscribe to or redeem from a hedge fund with a significant amount of non-exchange traded assets, how do you have confidence in the Fund’s Net Asset Value (“NAV”)? You may pay too much on the way in and sell for too little on the way out.

- An evergreen fund structure, like a hedge fund, should be administered by an independent third-party fund administration firm. If not, it is a significant red flag that necessitates further scrutiny.

- Assuming an administrator is in place, what is their process for valuing Level III securities? Ideally, a firm that specializes in valuing illiquid assets is engaged to price these assets, e.g., Houlihan Lokey, Alvarez, and Marsal, or Duff & Phelps(now Kroll), on an annual basis. The date at which these assets are valued, e.g., 12/31, should coincide with the date that the Manager 1) assesses the performance fee and 2) allows investors to enter/exit the Fund.

- Walk through the valuation process with both the Manager and the administrator. Is the administrator’s description of the valuation process consistent with the Manager’s description? If not, dig further.

2. If you are considering investing in a Private Equity, Real Estate, or Venture Capital Fund, how do you have confidence in the Manager’s track record if the underlying positions are internally marked? The internal rate of return (“IRR”) generated from unrealized positions may differ materially from the realized IRR.

- If the Manager is responsible for valuing a Fund, which is common in Private Equity, Real Estate, and Venture Capital, then assessing the degree of independence from the investment team in the pricing process is important. In these types of situations, the pricing process should be driven by the accounting and finance teams, not the investment/deal teams given the inherent conflict of interest for deal professionals marking their own portfolios.

- Does the Manager have a valuation policy that is enforced by a valuation committee where the majority of the committee’s constituents are not on the investment team? Having a valuation policy that clearly outlines how a Fund’s assets are valued is essential because it provides a valuation framework that can be followed regardless of the investment environment. Furthermore, the establishment of a committee to review and approve valuations helps ensure that a consistent valuation process governed by a valuation policy is adhered to.

- Who owns the portfolio company valuation models, the accounting team, or the investment team?

- Who is responsible for updating the valuation models with results from the underlying portfolio companies, the accounting, or the investment team? The pricing models for Level III assets should be owned by the accounting team or valuation agent as opposed to the investment team. Key inputs driving valuation models should remain consistent between accounting periods and changes should be approved by a valuation committee.

- Has the Manager engaged a third-party valuation firm? If so, do they 1) independently value the underlying assets and 2) are the values they arrive at used to calculate the Fund’s NAV? Or, conversely, does the valuation firm simply provide assurance that the Manager’s internal process for valuing the underlying assets is consistent with industry valuation practices, e.g., IPEV.[xv]The former is preferred over positive assurance.

- Walkthrough a valuation example with a Manager. Understand who was responsible for updating the valuation model. Review the valuation model and assess to what degree the assumptions driving the model changed. For example, was the set of representative transactions or public peers changed? Did key assumptions in the DCF model change? If so, why, and how were these changes approved? Did the relative weightings assigned to primary valuation processes change? Is the model’s ultimate valuation output consistent with the portfolio company’s value on the Fund’s financial statements?

3. If the underlying assets in the Fund were publicly traded, would they exhibit materially different volatility and correlation statistics? If so, is the Fund’s valuation process potentially creating a false sense of security?

- Valuations in public equity markets influence the value of privately held companies. Therefore, if the public markets have undergone a volatile period, e.g., the first quarter of 2022 where the total return for the Nasdaq Composite and S&P500 was -8.9% and -4.6%, respectively, then, all else equal, the valuations for privately held companies should also decline to some degree.

- It is instructive to compare the valuation of a Fund’s Level III assets to the returns seen in public equity markets during periods of heightened market volatility. All else equal, they should be positively correlated. If not, dig in. The Fund’s returns may be smoothed. [xvi]

- Does the Manager produce a valuation gap analysis where they compare the valuations of portfolio companies in the preceding accounting period to the value at which the portfolio company was realized? This type of analysis can highlight if there is a systematic valuation bias.

Valuations for Alternative Investments Closing Thoughts and Examples of Current Trends:

Beginning in 2017, a transition occurred that Managers of closed-end fund strategies, e.g., real estate, private equity, and venture capital, began to offer evergreen funds in addition to their existing closed-end funds. The primary benefit to investors of the evergreen relative to the closed-end vehicle was the deferment of taxes. This was particularly relevant in real estate funds where Managers could sell a building and instead of realizing a capital gain, enter into a 1031 exchange and reinvest the gross proceeds in a property(s) of like kind with equal or greater value. [xvii] However, as illustrated in our opening hypothetical and further discussed below, valuation becomes a material concern when investors can come in and out of a Fund at a price that is predicated on the FMV of the Fund’s illiquid Level III assets. Furthermore, the Manager, in most cases, is taking an incentive fee at year-end that is based on both realized and unrealized gains. With this dynamic in mind, below is a brief synopsis of valuation scenarios an investor should consider when evaluating open-ended funds that hold a significant amount of Level III assets:

- Capital Appreciation vs Income:From a valuation perspective, the nature of the underlying asset matters. For example, a mature, rent-generating, apartment building is easier to value than a brand-new development that is still in the leasing up phase. Likewise, a mature private company, that pays a dividend or has physical assets on its balance sheet that can be priced, is easier to value than a seed, start-up, stage company that often is pre-revenue. In these hypotheticals, the mature assets usually generate a larger proportion of their overall gains from income while gains from the earlier stage assets are more based on capital appreciation. From a valuation perspective, income-generating assets are easier to value than assets based on capital appreciation, because the valuation is less dependent on an assumed future terminal value. Therefore, investors analyzing evergreen vehicles that hold illiquid assets might find it easier to gain comfort with Funds holding predominantly income-generating assets, e.g., core real estate, self-liquidating assets (royalty streams), and private credit, rather than assets predicated on capital appreciation, e.g., venture capital.

- Valuation Date vs. Capital Activity:The Fair Value Measurement section discussed the concept of a determination date, i.e., the date at which a value for a Level III asset is determined. Typically, this is calendar year-end. If a Fund 1) hires an independent valuation agent to value an asset at yearend, and 2) has an auditor audit the Fund as of the same date, then an investor can generally have more comfort that the marks are closer to a theoretical fair market value. If this is the case, then it is helpful to have the date at which a Fund allows capital activity to occur, i.e., investors subscribe into and redeem out of a Fund, coincide with that determination date. This provides the situation where new investors, exiting investors, and remaining investors can get comfort that the price of the Fund, and therefore the price they are buying in at, selling at, or being diluted at, respectively, is fair and reasonable. On the other hand, if the Fund provides for capital activity to occur on a date that is far removed from the determination date, e.g., 6/30 or 9/30, then the price at which investors transact will be further removed from fair market value. This could advantage one group over another. When possible, investors might prefer to invest in Funds where the determination date and capital activity date co-inside with one another.

- Valuation vs Positive Assurance:Some Managers hire valuation consultants to provide “positive assurance” rather than an independently calculated price. While this may seem like semantics, the difference is important. If a valuation consultant is engaged to value an asset, then the valuation firm will typically maintain their own models, independently reach out to the underlying companies to receive updated financials and then price the asset based on information they received directly from the portfolio company. However, if a valuation agent only provides positive assurance, they are merely stating that the valuation assigned by the Manager is “reasonable” based on supporting materials that they also received from the Manager. Not only is this a circular reference (comparing a value received from a source with supporting information received from the same source), but it fails to mitigate many of the conflicts of interest inherent in having a Manager mark their own book. If only positive assurance is provided, then further diligence on the independence of the valuation process is key. For example, is there a valuation committee or valuation policy? If so, what is the makeup of the valuation committee in terms of deal vs accounting teams?

Let us now revisit the hypothetical introduced at the beginning of this whitepaper. During the due diligence process, we learned that 1) the Manager did not engage a third-party administrator nor 2) did the Manager use an independent valuation firm to mark the Fund’s Level III assets. However, we also discovered that the Manager 1) had a valuation committee that included several voting members not on the Fund’s investment team, and 2) had a purposeful valuation process where the valuation committee reviewed relevant changes to the valuation models covering Level III assets. This example underscores the idea that an assessment of a Firm’s valuation practices is not always clear-cut. In this situation, where you have aspects of the valuation process that are, and are not, consistent with industry best practices, you must delve further in the hopes of arriving at a reasoned decision as to whether perceived deficiencies in the valuation process are sufficiently mitigated. For example, do the operational risks of not having a third-party administrator and valuation agent outweigh the benefits of investing in the Fund? Does the Manager’s existing process, of having a valuation committee and defined valuation process, mitigate the previously identified risks? The answer is not obvious and ultimately comes down to an investor’s appetite for taking on potential operational risk. What is important, is that the investor is made aware of the potential operational risks so they can make an informed decision based on their particular risk appetite.

Upcoming Paper – Related Party Transactions

Our next paper will delve into related party transactions. These types of transactions create conflicts of interest for the Manager and can lead to situations where the Fund pays more for a service than it otherwise would if an independent third party was offering it. Related party transactions occur more frequently than many investors realize in the alternative investment space. It is important that investors understand how a Manager mitigates the inherent conflicts involved with these transactions.

If have any questions about valuations for alternative investments or would like to learn more, please contact John Canorro at jcanorro@pathstone.com or Chris Carsley chriscarsley@kirklandcapitalgroup.com.

Please see the PDF version of this article for important disclosures and citations. This article, The Importance of Valuations for Alternative Investments, was written for and published on the CAIA blog.

Authors

Chris Carsley CFA | CAIA: Chief Investment Officer & Managing Partner, Kirkland Capital; Group & Chief Investment Officer & Managing Partner Arch River Capital

John Canorro CFA | CAIA: Director of Operational Due Diligence, Pathstone